New York City is about to have its first ever ranked choice elections. This post is going to be a bit different compared to the ones I’ve previously written.

Here we’ll discuss three different voting methods. First, we’ll talk about plurality elections1, the system used in previous New York City elections, and the most common electoral method. Then we’ll talk about instant-runoff voting (IRV henceforth)2, the new system being used by New York City in the primaries, and how most other ranked-choice elections are run. Finally, we’ll talk about the Condorcet method_, a method that I will argue is better at electing a candidate than plurality and IRV.

Let’s dive in!

Plurality voting

Plurality voting is the system that you probably think of when you think of voting. The idea is very simple. Everybody casts a vote for one person, then the votes are tallied, and whichever candidate has the most votes wins.

Mark the oval next to the candidate who you would like to vote for. Vote only once.

| Candidate | |

|---|---|

| ◯ | Ada Lovelace |

| ◯ | Sophie Germain |

| ◯ | Grace Hopper |

| ◯ | Hedy Lamarr |

| ◯ | Margaret Hamilton |

Now, plurality voting has a lot of advantages. It’s fast, you can count votes super quickly, and get results quickly after votes have been cast. It’s also very simple to understand, which means that people can vote easily. You simply mark the candidate who you like the best.

There are; however, many downsides to plurality voting. First, voting for someone who may not be popular is a huge risk. Let’s say candidates A and B are the front-runners in the race; however, your favorite candidate is candidate C, and your second favorite is candidate B. Candidate C has basically no chance of winning, regardless of whether you vote for them. By voting for candidate C, you’re taking away a vote that would potentially mean more if you voted for candidate B.

One other downside is “splitting the vote.” This is what actually led to the party system that we have here in the United States and around the world. Let’s say that candidates A and B have similar ideologies, and candidate C has a different ideology.

The way that our society has solved this is by holding primary elections. First, we hold an election between the supporters of candidate A and B. Candidate B will win the primary, then, candidate A tells all of their supporters to vote for candidate B. Therefore, with the supporters of candidate A, candidate B can beat candidate C.

Now, even though candidate B won the election, candidate A’s supporters are happier than they would be if candidate C had won the election, which would have happened in the initial situation. Candidates A and B would have “split the vote.”

What’s interesting, is that with primaries, plurality voting becomes a sort of collective ranked choice! Collectively, the party determines that they would prefer a specific candidate, even if it isn’t their favorite one (candidate B in this example), to another candidate (C in this example). This post isn’t about politics, it’s about math, but I’m going to make one political statement here. I dislike the party system that we have in the United States, because it promotes extreme ideologies, and prevents centrist ideologies from prevailing. In fact, George Washington warned about this back in 1796:

[The spirit of the party] serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.3

Anyway! I digress. Back to math!

With systems like this, people end up writing in candidates and throwing away their votes. This is why we’re starting to introduce ranked-choice systems, such as IRV.

Instant Runoff Voting

Instant Runoff Voting (IRV) is one of the simplest forms of ranked-choice voting, and it’s what’s being used in the upcoming NYC primaries. It aims to remedy some issues with plurality voting, but it certainly isn’t perfect.

Rank up to five candidates in order of preference. Ranking a second, third, fourth, or fifth choice does not affect your first choice candidate, or any of the candidates ranked above them. You do not need to rank all candidates for your vote to count. Vote only once per row and only once per column.

| Candidate | Preference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |

| Ada Lovelace | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Sophie Germain | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Grace Hopper | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Hedy Lamarr | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Margaret Hamilton | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

IRV is actually a simplified version of another voting system called Single transferable vote (STV), but STV is designed for electing multiple people. It’s actually fascinating, and I highly suggest reading more about it.

IRV is pretty simple to understand. Voters rank the candidates in order of preference. Everybody’s first choice votes are then counted.

Next, we take the person in last place, and eliminate them. Everyone who voted for that person now is voting for their second choice. This repeats until there’s only one person left, and when there’s only two people left. After that, it’s a head-to-head election. The person with the most votes wins.4

Let’s look at our election from before. Note that this is quite simplified, but the same principle applies, just on a larger scale. We’ve established that people who like candidate A tend to also like candidate B, and people who tend to like candidate B tend to also like candidate A, so for simplicity’s sake, let’s assign ballots to each candidate:

Now, we eliminate candidate A because they have the fewest votes. We reallocate the votes for candidate A:

Now it’s a head-to-head election between B and C, and we can see that candidate B wins.

One thing that IRV is great at is resisting gamification. The ranking of any candidate does not affect any candidate above them, and it’s beautiful in that regard. Your vote for any candidate literally is not considered until the candidates above them are eliminated.

One of the biggest reasons that people are opposed to ranked choice voting is an increased susceptibility to gamification5, and I get that. Ranked choice voting is this big black box to a lot of people. They simply don’t understand how it works. But here’s the thing—IRV is easy to understand6.

Unfortunately, the Condorcet method is a bit harder to understand, but I’d make the argument that it’s less important that a specific method is easily understandable, and more important that it elects a candidate that most people would be happy with. Unfortunately, IRV can sometimes fail to do that.

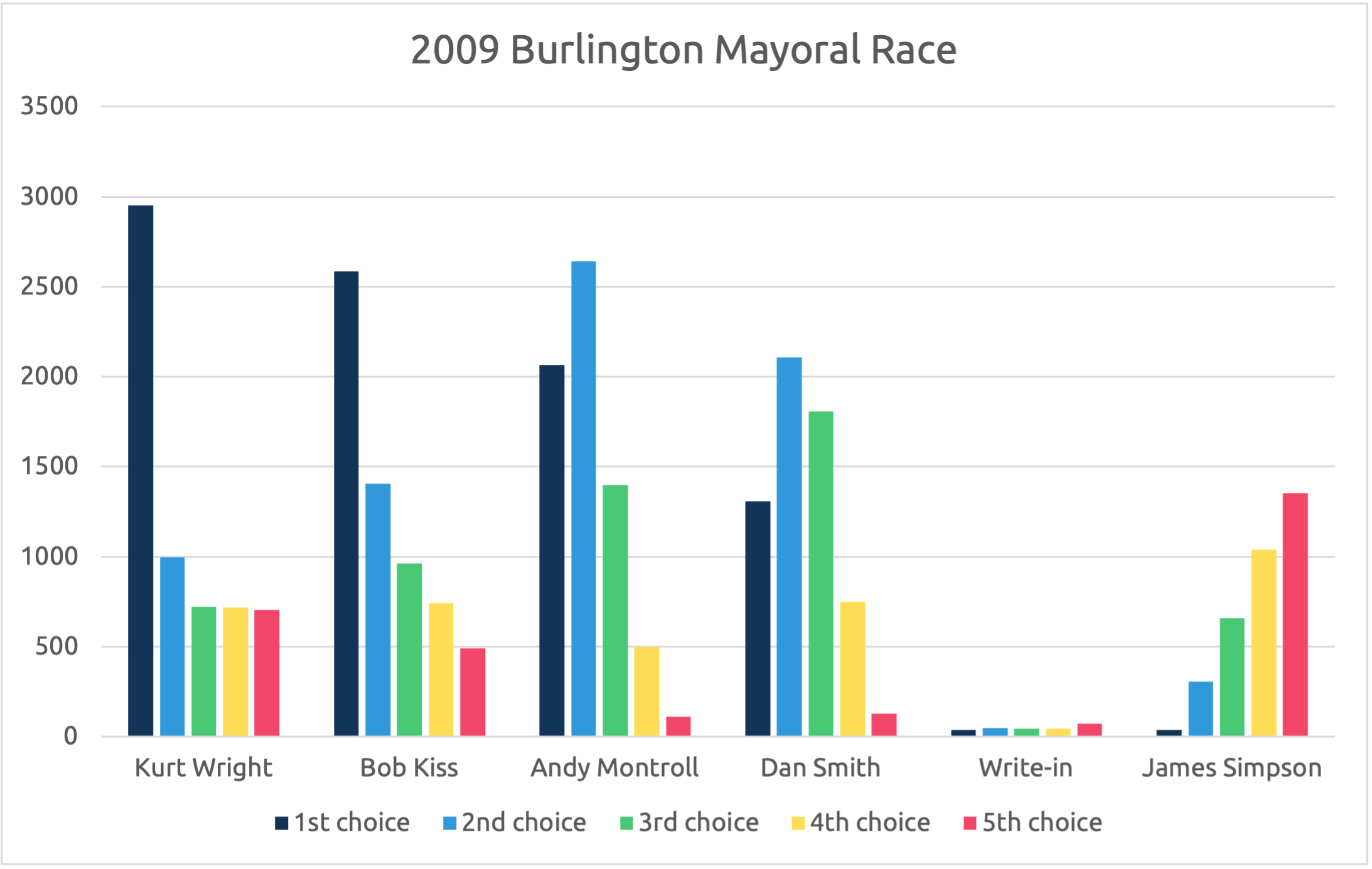

Let’s look at the 2009 Burlington, VT mayoral election, which was conducted via IRV. The chart below shows the number of ballots submitted that ranked each candidate first, second, third, fourth, and fifth.

Ranking by candidate in the 2009 Burlington, VT mayoral election.

Bob Kiss won the election by about 300 votes in the last round of IRV, but, the data tells that maybe the people would have preferred Andy Montroll. In fact, all three methods that we discuss come up with different winners for this election. With a plurality election, Kurt Wright would have won, and with IRV, Bob Kiss wins. But the third method we’ll discuss, the Condorcet method, shows pegs Andy Montroll as the winner.

Condorcet Voting

Looking back at that 2009 Burlington mayoral election, it seems like a lot of people would have preferred Andy Montroll. He had a strong 1st choice showing (ranking 3rd overall in terms of 1st choice), and an even stronger 2nd choice showing.

Rank five candidates in order of preference. You may give multiple candidates the same rank, but not ranking a candidate is equivalent to ranking them last. Vote only once per row.

| Candidate | Preference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | |

| Ada Lovelace | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Sophie Germain | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Grace Hopper | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Hedy Lamarr | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

| Margaret Hamilton | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ | ◯ |

Meanwhile, lots of people like Bob Kiss or Kurt Wright; however, they have very low second, third, fourth, and fifth choice showings. This means that more people would have preferred Andy Montroll to both Bob Kiss and Kurt Wright. Just a year later, Burlington repealed IRV, mainly due to issues with this 2009 election.

One way of combatting this issue is to use the Condorcet method. Any voting system follows the Condorcet method if, whenever one exists, a Condorcet winner is declared to have won the election. A Condorcet winner would win against any other candidate when using a plurality election.

There are several ways of picking a winner when a Condorcet winner does not exist7, so there are many voting systems to implement the Condorcet method.

Marquis of Condorcet

Artist unknown

The Condorcet system was named after Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet, who did a bunch of voting-related research in the 18th century. It is; however, important to note, that the first known Condorcet system was devised by Ramon Llull.

He was a decently cool guy, he promoted ideas like gender equality, and was one of the first enlightenment thinkers to propose women’s suffrage in the new republic.

To quote one of his writings:

The rights of men stem exclusively from the fact that they are sentient beings, capable of acquiring moral ideas and of reasoning upon them. Since women have the same qualities, they necessarily also have the same rights. Either no member of the human race has any true rights, or else they all have the same ones; and anyone who votes against the rights of another, whatever his religion, colour or sex, automatically forfeits his own.8

So, he seemed to have some pretty cool (and unpopular at the time) social beliefs. Anyway, let’s talk about Condorcet voting! The basic concept is that, rather than running one election, you run a head-to-head election between each candidate. Let’s say we have 6 people, each voting for their favorite ice cream flavor. They’re choosing between chocolate, vanilla, coffee, and strawberry (eww).

They submit the following ballots:

| # Ballots | 1st choice | 2nd choice | 3rd choice | 4th choice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Chocolate | Vanilla | Coffee | Strawberry |

| 11 | Vanilla | Coffee | Strawberry | Chocolate |

| 8 | Strawberry | Coffee | Chocolate | Vanilla |

| 5 | Chocolate | Coffee | Strawberry | Vanilla |

| 2 | Strawberry | Chocolate | Vanilla | Coffee |

(By the way, anyone who didn’t rank strawberry last is objectively incorrect)

Now, let’s run head-to-head elections between each of the candidates. We do this by matching taking every set of 2 candidates, then counting the number of ballots where one was ranked above the other, then the candidate who has higher rankings runs that “round-robin” round.

Let’s run it!

Winners are marked in bold, and the number of votes for each is marked in parenthesis.

| none | chocolate (32) / vanilla (11) | chocolate (24) / coffee (19) | chocolate (22) / strawberry (21) |

| vanilla (11) / chocolate (32) | none | vanilla (30) / coffee (13) | vanilla (28) / strawberry (15) |

| coffee (19) / chocolate (24) | coffee (13) / vanilla (30) | none | coffee (33) / strawberry (10) |

| strawberry (21) / chocolate (22) | strawberry (15) / vanilla (28) | strawberry (10) / coffee (33) | none |

Notice that chocolate beats every other ice cream flavor in the elections? This makes it the Condorcet winner!

It is important to note that it doesn’t matter how many of your round-robin elections you win, only if you win all of them. Not all elections have a Condorcet winner, and generally, if an election doesn’t, another method is used (like IRV).

Does it matter

I wrote all of this stuff about different voting methods, but then I wondered… does it matter? I wanted to find out.

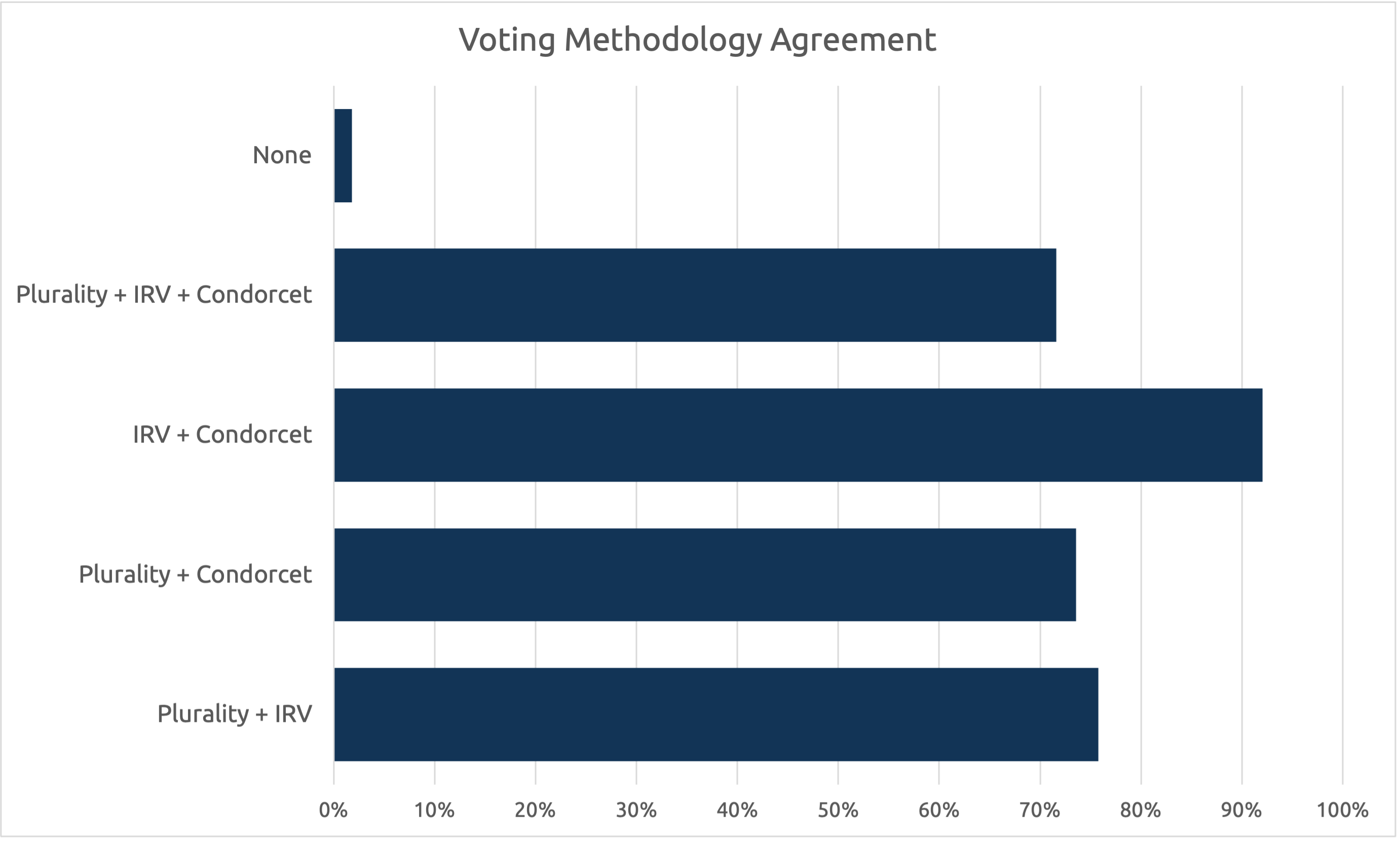

Here’s what I did. I wrote a program, ran 10,000 elections with 10,000 ballots and 3 candidates each. Then, I counted the ballots in each election using 3 methods:

- Plurality

- IRV

- A Condorcet method called the Schulze method.

I then measured how often these methods agree with each other. Only about 2% of the time do you get different results from Plurality, IRV, and Condorcet (like the Burlington, VT election earlier).

Condorcet is hard. It’s hard to understand, and it’s hard to count. It is by no means the solution to all voting issues, but for me, I believe that electing the best candidate is more important than the layperson understanding the voting method, and is more important than counting quickly.

Others might disagree with me, and this isn’t a political post, but that’s why I think that we should be using Condorcet voting, rather than IRV or runoff voting.

-

Also known as first-past-the-post (FPTP), single-choice voting, simple plurality, relative majority, or simple majority, because humans are bad at naming things. ↩

-

Also known as alternative vote (AV), preferential voting, and often just simply as ranked choice voting though that can also refer to other voting systems. ↩

-

Farewell Address. George Washington (1796). National Archives: Founders Online. ↩

-

There’s actually a bunch of shortcuts you can take to make this faster. First, if at any point, any candidate has ≥ 50% of the vote, they already won. There’s no way for another candidate to take a majority at that point. You can also do some fancy math and eliminate more than one candidate per round, and still get the same winner, but I won’t go into that. ↩

-

At least according to my original research™. ↩

-

Don’t worry if you don’t understand it. I promise it’s not your fault. Sometimes people learn things in different ways, and it might be easier for you to learn differently. This video from the New York City Board of Elections explains IRV in a more visual manner. ↩

-

This is called the Condorcet paradox, also known as the paradox of voting or the voting paradox (not to be confused with Arrow’s paradox, something totally different). Essentially, in an election with candidates A, B, and C, (or any number of candidates ≥3), the majority of voters can prefer candidate A over candidate B, candidate B over candidate C, and candidate C over candidate A, even if that cannot be said of any individual voter. ↩

-

Condorcet, Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat. Condorcet: Political Writings. Edited by Steven. Lukes and Nadia Urbinati. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ↩