I decided to run a small CTF1 for high school students. It was a lot of work, but it was definitely worth it. I called it HackDalton, after my school. HackDalton was my senior initiative (for non-Daltonians, that is a fancy way of saying a big project that seniors do at the end of the year), and I was lucky enough to be advised by the wonderful Charlie Stewert.

HackDalton was a ton of fun to run, with a ton of facets. One of the first that comes to mind is problem writing. HackDalton had 15 problems among 3 categories

- General Knowledge (general)

- Web Exploitation (web)

- Binary Exploitation & Reverse Engineering (BE/RE)

The General Knowledge category was the easiest to write problems for, just because there were so many possibilities. I decided to use the first few problems in the general category to teach people about technologies that they would need for the rest of the problems, as HackDalton was targeted at beginners. The first problem I wrote was called “Hello, netcat,” and was just designed to teach people about the netcat tool2. One simply connected with nc problems.hackdalton.com 17156, and they received the flag. I thought that that was a good way to start, as netcat was a tool needed for a lot of the other problems.

I also wrote problems involving grep, HTTP3, steganography4, and PGP. I thought that all of these problems (with the exception of the stego one) would teach important skills to every participant. When I was writing problems, I made a few rules for myself, the most important being that I wanted all the problems to be related to real-world vulnerabilities. I didn’t want to make anything up just for HackDalton. HackDalton was supposed to be a learning experience, so I thought that people should actually learn useful things from it. I also had to address the big difference in skill level between participants. Some students were advanced programmers, and others were just getting started. I decided to run a “live help” forum during the competition for anyone who needed help (it ran on Discourse).

Live help was an interesting aspect of HackDalton. Because it was designed to be more of a learning experience than a competition, I wasn’t really afraid to give too much away. After all, anyone could access the help forum and ask any questions that they wanted to, in fact, I continuously encouraged people to use it throughout the competition. Through the helpdesk, I gave hints to plenty of participants who were stuck! HackDalton was only one day long, so there wasn’t much time for participants to take a break or do any of the other typical “get unstuck” tactics.

I also tried to write some beginner problems in each category. In the web category, I wrote a problem called “let me in 1,” which just required opening the developer tools to see some client side security code in a <script> tag at the bottom of the page:

$("#submit").click(function () {

if ($("#username").val() == "admin" && $("#password").val() == "superSekret1!1") {

showFlag();

return false

} else {

alert("Invalid login")

}

});

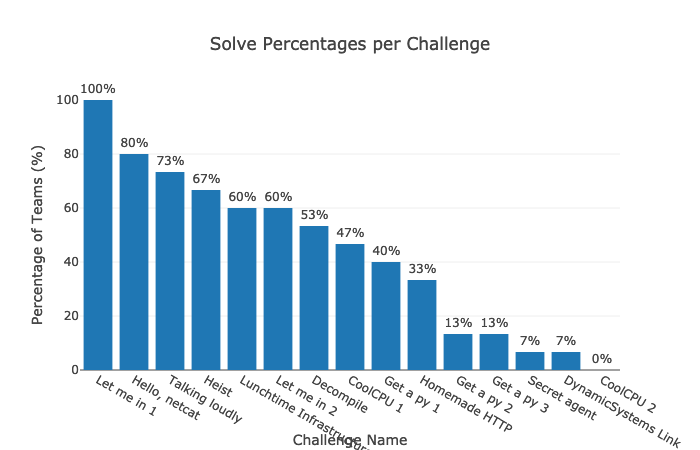

As you can see, the username was admin and the password was superSekret1!1. Something interesting I found about this problem, in particular, was the number of solves.

As you can see, the problem “Let me in 1” had the most solves, but I had intended “Hello, netcat” to be the easiest. One potential reason for this is that people are more familiar with a web browser than the command line. Almost everyone has at some point or another, either intentionally or accidentally, opened the developer tools in their browser. All this problem required was using the developer tools to find that code block. In fact, I even added it as a free hint to the problem

My friend got locked out of his website. Can you help him get back in?

http://problem-letmein1.hackdalton.com/

Hints

- Try using the “View source” option in your browser

Every team that was able to solve at least one problem (I’ve been calling these “Active teams”) solved “Let me in 1,” while “Hello, netcat” only had an 80% solve rate for active teams, though nobody asked for help on either problem (though someone did ask for help installing netcat, I pointed them to our handy-dandy Windows Subsystem for Linux install guide). I found this interesting, and hypothesize that this is due to a combination of two reasons.

- Teams were embarrassed to ask questions about the first 2 questions because they were meant to be “easy.” Honestly, as someone running the competition, I would have much rather they ask questions than just give up.

- The type of team that was unable to solve the question was generally inexperienced. They may have just decided that this type of competition “wasn’t for them” when they were participating

. As an organizer who strived to build a CTF inclusive of all skill levels, this makes me really sad.

. As an organizer who strived to build a CTF inclusive of all skill levels, this makes me really sad.

Shifting topics here a bit, another thing that I struggled with was funding. Dalton, as a policy, does not fund Senior Initiatives, so I was on my own. I decided that it would be easiest to reach out to companies to ask for resources. I didn’t offer a prize in order to reduce costs. I reached out to DigitalOcean and Linode to ask for server resources, and I heard back from Linode the next day! Linode became an amazing sponsor for HackDalton to cover practically all server costs! I also reached out to my friend (@thatoddmailbox) who I know runs an email server, and asked for him to configure email for @hackdalton.com addresses in exchange for a promotion for his company PartBolt. He happily accepted (thanks @thatoddmailbox!).

I think the moral of the story there is to reach out to companies! Even if you think that they’ll say no, that’s the worst that can happen. Many companies have forms to fill out to request a sponsorship, but not all do.

On the actual day of the competition, there were lots to do! I woke up that morning and prepared a PDF with a list of all the problems and the links to them in case the game server went down. I came very close to using it but luckily didn’t. I set up a schedule for the day:

| Time | Event | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 10:00 AM | Opening remarks | live.hackdalton.com |

| 10:30 AM | Competition starts | game.hackdalton.com |

| 12:30 PM | Lunchtime Infrastructure Chat | live.hackdalton.com |

| 5:00 PM | Competition ends | game.hackdalton.com |

| 5:00 PM | Closing remarks | live.hackdalton.com |

I started my remarks a little late, to give people time to get set up. In the meantime, I showed a little animated screen that said “Welcome to HackDalton! We’ll get started shortly,” and played some music (which actually turned into a meme during the competition, and I finally got it out of my head!)5.

For the live parts, I used Zoom to host a webcast. Personally, I have big issues with Zoom (they have questionable security practices and use malware-like practices in their installer and software), though I decided to use it anyway because of how widely it is used. I also streamed the live segments to YouTube and prominently featured a Join from Browser link (you can join any Zoom meeting from your browser by going to https://zoom.us/wc/join/<MEETING ID>).

The opening remarks ended around 10:20 AM (slides, video), giving me 10 minutes to prepare for the competition. Unfortunately, around 10:22 AM, game.hackdalton.com went down. I immediately started debugging (and preying ![]() ). I first ssh’ed into the server and ran

). I first ssh’ed into the server and ran htop, and saw very high CPU usage. I tried restarting the server, which didn’t help. By then it was probably 10:27. Alex Studer (@thatoddmailbox) was helping me debug, and he noticed something interesting in CTFd’s source code. Their Dockerfile contained the line:

ENTRYPOINT ["/opt/CTFd/docker-entrypoint.sh"]

meaning that the docker-entrypoint.sh script is run to start the server in a docker container. We weren’t running CTFd in a docker container, but this script may give us clues to optimizing CTFd. The entrypoint file does a bunch of stuff, including updating the database, configuring a secret key, and checking the database, then starts the server with these commands:

# Start CTFd

echo "Starting CTFd"

exec gunicorn 'CTFd:create_app()' \

--bind '0.0.0.0:8000' \

--workers $WORKERS \

--worker-tmp-dir "$WORKER_TEMP_DIR" \

--worker-class "$WORKER_CLASS" \

--access-logfile "$ACCESS_LOG" \

--error-logfile "$ERROR_LOG"

Most of this is pretty boring, except for one flag passed to gunicorn, which I didn’t have in my systemd service file: --worker-class. Earlier, the script contains a few lines setting up some variables:

set -eo pipefail

WORKERS=${WORKERS:-1}

WORKER_CLASS=${WORKER_CLASS:-gevent}

ACCESS_LOG=${ACCESS_LOG:--}

ERROR_LOG=${ERROR_LOG:--}

WORKER_TEMP_DIR=${WORKER_TEMP_DIR:-/dev/shm}

The WORKER_CLASS variable is set to gevent. Upon adding the --worker-class gevent flag to my systemd service file and restarting the service, CTFd came back online and was zooming ![]()

![]() . @thatoddmailbox and I now joke that

. @thatoddmailbox and I now joke that --worker-class gevent is the “magical fix everything flag,” that was somehow missing from the CTFd documentation. game.hackdalton.com went back up at (literally) 10:29 AM, with a scheduled 10:30 AM start time. I was soooooo relieved.

Following that hiccup, it was pretty smooth sailing ![]() . Overall, I’d say that HackDalton was a major success, and I hope to run something like it again soon!

. Overall, I’d say that HackDalton was a major success, and I hope to run something like it again soon!

-

“Capture the flag”: A type of programming competition. Essentially, each team is given a set of problems that they have to “break in to.” These can be websites, programs, etc, and they each have a “flag” (an alphanumeric string) hidden inside. ↩

-

Netcat, often written

nc, is a command line tool that lets you open TCP connections to different servers. If that was a bunch of gibberish to you, don’t worry — it’s not very important. ↩ -

I had an interesting internal debate about where my HTTP problem should go. It required hand-writing HTTP requests, which is pretty webby, but I finally decided on general knowledge (mainly because the OCD in me wanted 5 problems in each category). ↩

-

I actually learned a lot about steganography for this problem — it turns out there are a whole bunch of different types! ↩

-

“Werq” by Kevin MacLeod (incompetech.com) Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 4.0 License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ↩